Retired From Sad, New Career in Finding Excuses to Talk About Mitski All the Time

- tashfaaa

- Sep 15, 2022

- 16 min read

Updated: May 18, 2023

The urge to analyse David Bowie’s star image was rather strong with this one, but there’s a 99% probability I would have ended up going down a rabbit hole of re-watching eclectic childhood favourite films featuring him instead of working productively, so I didn’t take any chances. (Which is not to say that I did achieve optimum productivity, but let’s not think too much about that. Or the existential crisis that comes with calculating how many assignments you can finish in twenty-four hours.)

Anyway, if you haven’t noticed already, I’m a Mitski enthusiast first and a human being second which is why we’re here; using Richard Dyer’s model (and Michael R. Frontani’s adaptation of it to coincide with defining a music star’s image), I’ll be outlining Mitski’s star image by exploring media texts like promotion, publicity, work product (music), and criticism and commentaries*.

*From what I understand, this last category comprises reviews and commentaries about a star and their work primarily after their death; since Mitski is very much alive, much to the dismay of therapists all around the world, I’ll instead be generally going over people’s perception of her work, reviews of her music, commentaries on her public image and/or persona(s), and fandom spaces, etc., currently in relation to star image.

My love for artists who put a lot of effort into creating intricate alter-egos and multi-layered narratives to accompany their albums is unparalleled; yes, my friends hate me for randomly lecturing them about David Bowie’s influence as seen in literally everything from Cowboy Bebop to Doctor Who, or the way Arthurian and biblical allusions shape MITO, the alter ego at the centre of DPR Ian’s albums. However, I’ve picked an artist whose star image has more of a subtle quality and charm, particularly in the way it is impacted by the singer's identity as an Asian American queer woman. Rather than an entirely superficial construction that merely serves as a promotional tool, Mitksi's star image becomes a projection and creative enhancement of her identity and the themes she wishes to highlight through her work.

Since Mitski is considered an indie artist, it can be said that her star image is an inventive one that is not necessarily forced onto her by her record label and does not entirely fit Dyer’s assertion that star images are constructed by institutions who are keen to benefit commercially in order to achieve success. Which is to say that what particularly fascinates me about her star image is how it represents an inherently anti-capitalist message that allows Mitski to assert and take control of her identity to discourage consumers from viewing the artist as a commodity.

(To balance things out, I'm hoping to explore elements from various artists' star images that stand out to me later on in a way that might help me further define the hypothetical artist I would like to portray in the advanced portfolio project eventually. This case study centred on Mitski will therefore serve as a comprehensive examination of subtle star images as well as their impact and significance in the digital world, while my later research on genres (codes and conventions, how certain artists' star images evokes their distinct genre, etc.) and other media elements will be more specific to the project itself.)

With all of that in mind, here’s an overview of Mitski’s evolution as an artist and the development of her star image over the years.

崩れてゆく前に / before you crumble

lush (2012)

Mitski Miyawaki, who performs under the mononym Mitski, cultivated her initial years of fame through Tumblr in a similar manner to earlier independent artists utilising MySpace. Miyawaki's rise to independent fame began with her entry into the independent music scene as a college undergrad through her first album Lush which is undeniably brimming with feminine rage.

In an interview with The New Yorker, the artist said:

“I spent all my teenage years being obsessed with beauty, and I’m very resentful about it and I’m very angry… I had so much intelligence and energy and drive, and instead of using that to study more, or instead of pursuing something or going out and learning about or changing the world, I directed all that fire inward, and burnt myself up.”

Lush, in the light of its quote, holds true to its name: a series of songs with unflinchingly vivid narratives and explorations of female rage in the face of being reduced to an object momentarily valued only for its beauty. I believe that these notions, encapsulated in the Japanese phrase ("崩れてゆく前に" or "before I collapse/crumble/fall apart") repeated in the first track of the album, are at the centre of the star image associated with her first album in particular.

Created and released when Mitski was a student in SUNY Purchase’s composition program, Lush virtually has no music videos; the music itself, therefore, shaped her star image during this era with its recurring motifs and themes that explore gender roles and their intersections with feminine desire and the transience of youth and beauty.

An example of this could be the fourth track on the album, "Real Men," which incorporates jazzy piano and straightforward lyrics, perhaps stylistically paying homage to Fiona Apple’s writing and way of performing. A clear commentary on toxic masculinity and how patriarchy shapes the way women perceive themselves and their positions in society, the song contributed greatly to Mitski’s music being viewed as a cathartic exploration of female rage and gender roles. The most streamed songs from Lush, Brand New City and Liquid Smooth, similarly contribute to this narrative which many fans on the internet would agree dominates Mitski’s debut album as well as the ones that followed:

"I haven’t thought about [Lush] for a long time. I think that record is all about me trying different things. It’s the most varied in terms of genre or style because it was my first album, and I took all these different songs I wrote at different times and put them in one record, as opposed to having focused time to write for it and just writing “an album.” I think for the first record, I was trying out all the different things I might want to do in the future. So yeah, I’d say “Brand New City” was I guess a precursor to the current stuff I’m working on."

— Mitski, ‘I don’t belong anywhere. That really affects how I write songs.’ Published in Chicago Reader.

Each track on Lush consists of haunting lyricism and discordant melodies, creating an unsettling mood that marked the beginning of the experimentation her later albums would go on to represent.

retired from sad, new career in business (2013)

A collection of songs for people who have probably had one too many crying sessions over the looming dread of growing up and dealing with adulthood, university applications, and capitalism all at once (*cough* me *cough*), Mitski’s sophomore album was also released while she was still in college and makes me wonder what sort of demon she sold her soul to in exchange for having her life together at the age of 22.

Stills from the music videos of: Because Dreaming Costs Money, My Dear; I Want You; Class of 2013; and Humpty.

With its series of primarily black and white music videos that could almost be mistaken for vignettes from a hypothetical indie coming-of-age film, Retired from Sad, New Career in Business contains songs that went on to become some of Mitski’s most popular ones. (Interestingly, the self-referential nature of these music videos could be considered a prelude to Mitski using performance art and artists as the subject of her future albums—another hint towards her developing star image.) It goes without saying that Gen Z’s “main character of an A24 coming-of-age movie” Spotify playlists continue to be incomplete without the tracks “Class of 2013” and “Because Dreaming Costs Money, My Dear” from this album. (Spotify playlists are the backbone of this blogpost, and I can’t tell if that’s a good or a bad thing, so let’s proceed and not think about it too much, thank you.) Evidently, the low-budget indie look of Retired from Sad’s music videos as well as the album's distinct themes contributed to attracting a young audience that views 'indie' as an aesthetic.

However, the relationship between internet aesthetics and Mitski’s music also had a detrimental effect on how people, particularly her caucasian audience, perceived her art. Propelled primarily by TikTok-driven hit “Strawberry Blond” around seven years after its initial release as a part of Retired from Sad, Mitski accidentally became a figurehead of the inherently white “cottagecore” aesthetic. In many ways, the fairly eurocentric world of cottagecore is an uncritical celebration of the tropes and spaces Mitski is commenting on in Strawberry Blond: cottagecore’s foundations are mainly white and include some questionable elements (e.g. the concept of homesteading, for instance, comes from the colonisation of Indigenous nations and still perpetuates that harm today), and the song has been subsumed by cottagecore to a degree where it’s associated with the aesthetic first and foremost in the public eye, erasing and whitewashing the undercurrent of racial pain present in the song—which is to say that most of Mitski’s later career would be spent trying to distance herself from such associations through her star image.

mitski & milhouse

bury me at makeout creek (2014)

Mitski’s third album and first release with the record label Double Double Whammy aligned with the quality of many of the label’s releases—strong melodies and honest, biting lyrics—but was simultaneously a departure from any familiar ground. Falling somewhere amid folk, pop, and breezy electric guitar rock, Bury Me at Makeout Creek doesn’t adhere to any one genre, and its opposition to genre conventions is what makes it so appealing. What we expect from a folk singer-songwriter, an artist on DDW, or a music composition major is none of what we get in Bury Me; what we get instead is a sublime mesh of these elements and a subsequent association of Mitski with unpredictability and versatility by her audience.

According to Mitski, Bury Me is the first album she promoted properly, e.g. through more well-developed music videos and a lot of live performances. This was particularly aided by the rich intertextuality in the album which contributed to fortifying Mitski’s image as a star whose work goes beyond just the surface level.

If you think the album’s name is silly, think again because it references a show some might consider one of the cornerstones of pop culture: The Simpsons. More specifically, it's a Milhouse Van Houten quotation; Bart Simpson’s blue-haired, bespectacled best friend delivers the line after being hit by a bus in the episode Faith Off.

Other instances of intertextuality in the album are perhaps a little less puzzling and more profound, for example, the influence of poets John Giorno and Charles Reznikoff on the content of tracks like “Texas Reznikoff.”

Moreover, this album's live performances employed more ominous choreography which has become a staple of Mitski's tours and a central motif in her star image:

Ultimately, the chaotic bricolage of seemingly unconnected visuals and themes in music videos like that of the first track, Townie, defines this album’s diverse nature which served the role of preparing Mitski’s growing audience for her other equally multi-faceted, nuanced and ambiguous records.

ode to growth

puberty 2 (2016)

Puberty 2 explores adulthood, queer desires, and coming to terms with one’s own identity against the backdrop of society’s expectations. The central metaphor of the album might be that one’s twenties, especially for marginalised communities, are almost like a second puberty. Mitski’s music does not abide by typical concept album tenets; however, despite lacking a clear protagonist and thematic narrative, it is clear that the emotional journey of entering adulthood and forming an identity for oneself is being conceptualised here.

This album understands how adulthood is spent learning to cope with, and eventually resist, the forces that enforce marginality on many. Mitski’s particular practice of creating nuanced stories within her music, like with characters such as Dan in the song Dan the Dancer, serves to protect her privacy, creating a space for semiotic explosions–which is another reason why so many fans are attracted to her lyrics, supporting Dyer's theory in the way her music and her life are kept separate while still embodying an intimacy that attracts fans and encouraging a sort of parasocial relationship between the audience and the star.

By constructing polysemic narratives, Mitski is much freer to play with and name intangible feelings related to marginalisation and the trauma that comes with it—Puberty 2 as an album effectively represents this. All of this is to say that the narratives at the centre of Mitski’s fourth album, amplified by promotion such as through music videos, may or may not have effectively drawn an audience of young adults living in a perpetual state of experiencing existential crises.

Her insistence on exploring themes of Asian American identity is also ubiquitous here, for example in the music video for Your Best American Girl, in which she displays her signature choreography too.

your best american/sad girl?

be the cowboy (2018)

It wouldn’t be wrong to claim that “Be the Cowboy” launched Mitski’s career to new heights. The 2018 album instantly became a TikTok favourite; needless to say, it was impossible to scroll through the app without hearing the solfege syllables and theatrical synths of “Washing Machine Heart’’ or the woeful repetitions of “Nobody” during this time. Now exposed to a larger audience, Mitski’s music also drew new interpretations—this essentially marked the fortification of and simultaneous opposition to her career’s supposed Sad Girl Era if you will.

Throughout her career, many have perceived Mitski and her music as the embodiment of the “sad girl” trope, particularly with the viral songs mentioned above. Some fans excessively pinned this single notion onto Mitski and her music, refusing to perceive her as being multidimensional. This completely dehumanises her as a person and disvalues all aspects of her identity beyond her music.

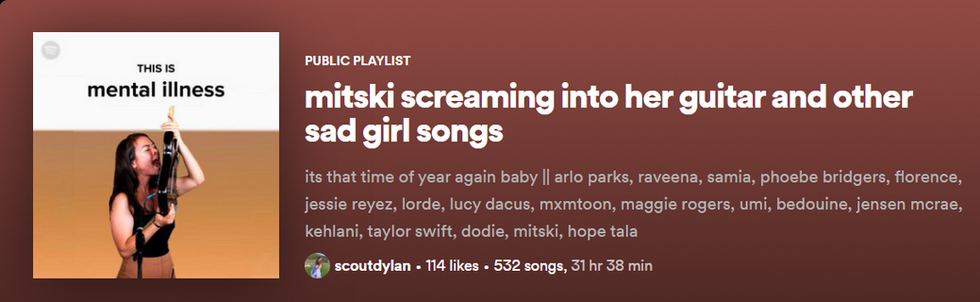

A great example of how this image (which the artist herself did not want to be associated with) was perpetuated by a large percentage of her fandom is the contribution of Spotify playlists; playing the role of what Jenkins might describe as being active consumers who aid the acceleration of participatory culture to a certain extent, her fans fueled the “sad girl” image by curating playlists that are centred around this theme.

Even the huge corporation itself has bought into the sad girl phenomenon with one of its most popular playlists:

The fact that the first two songs in it as of now are by Mitski only goes on to prove the point further—the power of publicity and fandom spaces in shaping an artist’s image, sometimes even against the will of said artist.

All of this is to say that a dynamic between the artist and consumers was created where Mitski and her music have been commodified to the point that ‘sadness’ is now viewed as a selling point of her career rather than as an act of expression. This aptly summarises the sort of impact an audience can have on how the masses perceive an artist, displaying an example of textual poaching by shaping their image in ways the musician might not even have intended. Mitski’s response to this situation (particularly through her live performances and the release of Laurell Hell) which had been developing over the years marked a major shift in her career, star image, and the themes highlighted in her work.

The Be the Cowboy Tour included dozens of brilliantly theatrical gigs. Working with the choreographer Monica Mirabile, Mitski cycled through female archetypes–including supposed coquette and housewife–on stage as she sang, posing across household furniture.

“I was dealing with being an object that’s looked at,” she noted in an interview with The Guardian. “Being a woman, an Asian woman, there are all these different projections that people put on me, and I guess the choreography was me trying to figure out how to deal with that. And playing with it: I would signify to people that I’m being sexual, but I would have a stone face.”

Through the eclectic and almost off-putting choreography of her live performances and music videos alike, Mitski seemed to be reclaiming and turning around the voyeuristic gaze of the media and the consumers of her art as if to remind them that she is the one in control.

The album's title and the persona that accompanied it also reflect this aspect of her star image. Mitski notes that “be the cowboy” was a mantra for self-confidence at a time when she didn’t always have it. In some ways, this echoes Solange’s sentiment around reclaiming cowboy iconography–articulating a need for marginalised people to adopt a cowboy-like attitude in regards to making space for themselves. Her music and music videos in this era thus question spectators about why they feel the need to ask permission for space, when as an individual they inherently deserve it.

the idea behind 'be the cowboy' in mitski's own words:

In a 2018 interview with NPR ahead of Be The Cowboy’s release, Mitski embraced her multitudes, a departure from the more passive nature of her past work:

“When I say cowboy, I'm talking about the Marlboro myth of a cowboy — the very strong, white male identity. And so as an Asian woman, I sometimes feel I need to tap into that to achieve things that maybe I don't believe I can achieve.”

She explains using the inherently white American myth of the cowboy as a persona to channel a sense of control and autonomy as an Asian artist in several interviews:

“What inspired [Be the Cowboy]?

I'm not the kind of artist who makes a thematic record. When I first start writing, I'm never thinking about the whole album concept — I'm just writing. But as I was writing this, I discovered a sort of pattern where I realised I was talking a lot about loneliness, and maybe feeling a little mad — not mad as in angry, but mad as in loopy. Also, I noticed I was playing with a lot of ideas about control, or just rather feeling that I didn't have control, so the protagonist or the main character feels like they want it but can't or don't have it.

From there, I started to shape this character. It's someone who is in me, but not who I walk around being all of the time. This woman who's very repressed or reserved, who feels powerless and therefore seeks power, or feels like she has no control over her life or herself, so she adamantly seeks to regain it. I went back a lot to the idea of the protagonist in The Piano Teacher, which is a French film by Michael Haneke that was adapted from the book of the same name. She really helped guide what I wanted out of the album, visually.”

— Mitski. Published in PAPER People.

Clearly, Mitski has a charm that goes beyond the reductive “Sad Girl” umbrella, and her latest album embodies her efforts to reassert this sense of control through her image and work once again.

soundtrack for transformation

laurell hell (2022)

Much to my (and many others’) dismay, Mitski decided to distance herself from music after Be the Cowboy. Dreading a time when the purpose of creating music would just be to keep the money flowing instead of to have a genuine creative outlet for herself, she announced her “last show indefinitely.”

Despite her resolve to stay away from the music industry, Mitski was soon reminded that because of her contract she owed her label, Dead Oceans, one more album. “I contractually had to release it,” she said, in an interview with Rolling Stone. “I just didn’t know whether I would ask the label to take it and keep me out of it, or I would actually go out and present it.”

“Laurel Hell,” the album that came out of that situation, embraces both Mitski’s deep reluctance to return to the music industry and her love of making music—a paradox that defined her star image during this era.

The album title itself perfectly underscores Mitski’s feelings about making music professionally. “Laurel Hell is a term from the Southern Appalachians in the US, where laurel bushes basically grow in these dense thickets. When you get stuck in these thickets, you can’t get out. Or so the story goes,” Mitski explained in an interview on the Zane Lowe Show. The notion of something as beautiful as the laurel flowers being dangerous enough to engulf someone beyond saving is reminiscent of her love of making music even though it hurts her.

Therefore, a recurring motif in this album’s lyrics and visuals alike is the idea of the reluctant artist. Most of Laurell Hell’s music videos exemplify the act of creating art as a messy, perilous one characterised by submission and exploitation. “Working for the Knife”, for example, epitomises the futility of creativity when one cannot express any autonomy under the weight of being yet another cog in a capitalistic machine.

Mitski mimes one last drag from a cigarette and then pointedly sheds her distinctly cowboy-esque outfit, leaving the cowboy behind to reveal an azure blue two-piece outfit. It’s a symbolic gesture and an explicit one; after her time away from the wanting eyes of her fans, the era of the cowboy is over. Another image of Mitski instead plays out in the rest of the video, in which she performs her increasingly disconcerting choreography that is actively inspired by Butoh—a type of post-war Japanese dance theatre that often involves slow, hyper-controlled motions, exaggerated facial expressions, and a fixation on hard emotions and absurdity—a cultural code one could argue successfully fascinates audiences, particularly in its homage to Japanese culture, making especially the Asian/Asian American audience feel closer to the star. Pitchfork's Eric Torres named "Working for the Knife" the best music video of October 2021, writing that her "forcefulness" was "cathartic" and "reveals the intense loneliness that comes with putting your whole self out in front of an audience that’s all too eager to consume every moment".

In holding up a mirror to those parts of Mitski’s audience that view her as a commodity, Laurel Hell reflected the perspectives of those of her fans who acknowledge Miyawaki’s positively multifaceted nature as an artist without objectifying her and allowed this renewed image to intimately reach large groups of people.

last notes

Mitski’s embodiment of star image is often unique in its nature, sometimes even contradicting Dyer’s theory. However, there are several other instances that are imbued with elements of this theory’s assertions.

For example, the singer-songwriter’s creativity and talent as a performer construct her as a tool for production within the media industry in many ways too, such as Mitski and David Byrne's duet "This Is A Life" which was created to be featured on the score for Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022). The representation of Asian Americans in a popular indie film featuring songs by artist’s like her attracted similar audiences for the singer and the movie alike. Combined, these characteristics support Dyer’s theory about stars as social phenomena, even when related to those who do not rely on acting.

When applying Dyer’s theory to Mitski, another significant aspect to discuss are the novelistic qualities of a character that make them interesting to the public. There are many that Dyer mentions, which could fill up another thousand words my sleep-deprived self won’t be able to handle, so here are a few: particularity, interest, and development.

In this case, Mitski is a great example, as she promotes individuality, highlights cultural diversity, and preaches acceptance, particularly in the way she uplifts the community of artists around her, attracting interest toward herself.

This excerpt from an article published in the New Yorker, i.e. a form of publicity, could be one example of this:

“The musician Sasami Ashworth told me that Mitski was “sort of a mother hen.” When Ashworth was about to go on tour without merch—she couldn’t afford any—Mitski told her she’d never make enough money just by performing in clubs, and immediately sent her five hundred dollars to have T-shirts printed. Ashworth also noted that Mitski is “very conscious of who she brings on tour—having opening acts she wants to uplift personally, financially, and professionally.” She went on, “Mitski doesn’t necessarily talk about feminism all the time on Twitter, but she has so many women of color and queer people working with her.” The two acts that opened for Mitski in 2016—Japanese Breakfast and Jay Som—are both fronted by Asian-American women. That triple bill was “sort of legendary,” Ashworth said.”

Lastly, the development of a character is important when describing a star or sign as described by Dyer because people want to know how said character grows, changes, and explores life. Like reading a novel, if the protagonist does not develop in some way, the plot becomes less relatable. It wouldn’t be incorrect to say Mitski’s character has been changing over a career that spans many years, finding new styles, personas, themes, and values and promoting new ideas with every different stage of her own life and her relationship with her art form. Therefore, I believe the she fits the mould of the “Star” of Richard Dyer’s theories.

Comments